The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) is already billions of dollars over budget and decades behind schedule. Not even its leaders can say how much more money and time it will take to complete

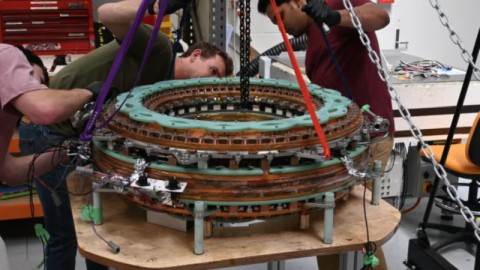

New Zealand startup OpenStar has created an experimental reactor, in which it was able to hold a plasma cloud with a temperature of about 300,000 °C for 20 seconds. According to the founder of the company, Ratu Mataira, to achieve such results They managed in just two years, while spending less than $10 million.

The team suggested original design of the reactor. Instead of external magnets, to hold The scientists used a levitating magnet located inside the chamber. Such The system is claimed to scale better than tokamak-type reactors because it is easier to modify.

Experts from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology institute highly appreciated the development of the startup and noted its high potential to accelerate the creation of a commercial version of the reactor. For further development project, the startup expects to attract up to one billion dollars of investment in the first quarter of 2025.

It could be a new world record, although no one involved wants to talk about it. In the south of France, a collaboration among 35 countries has been birthing one of the largest and most ambitious scientific experiments ever conceived: the giant fusion power machine known as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER). But the only record ITER seems certain to set doesn’t involve “burning” plasma at temperatures 10 times higher than that of the sun’s core, keeping this “artificial star” ablaze and generating net energy for seconds at a time or any of fusion energy’s other spectacular and myriad prerequisites. Instead, ITER is on the verge of a record-setting disaster as accumulated schedule slips and budget overruns threaten to make it the most delayed—and most cost-inflated—science project in history.

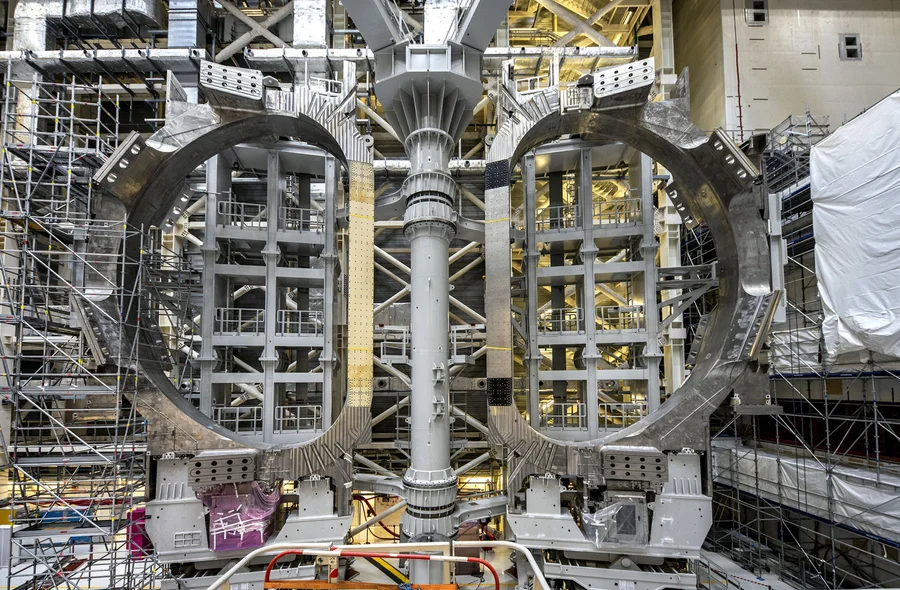

ITER is supposed to help humanity achieve the dream of a world powered not by fossil fuels but by fusion energy, the same process that makes the stars shine. Conceived in the mid-1980s, the machine, when completed, will essentially be a giant, high-tech, doughnut-shaped vessel—known as a tokamak—that will contain hydrogen raised to such high temperatures that it will become ionized, forming a plasma rather than a gas. Powerful magnetic and electric fields flowing from and through the tokamak will girdle and heat the plasma cloud so that the atoms inside will collide and fuse together, releasing immense amounts of energy. But this feat is easier said than done.

Since the 1950s fusion machines have grown bigger and more powerful, but none has ever gotten anywhere near what would be needed to put this panacea energy source on the electric grid. ITER is the biggest, most powerful fusion device ever devised, and its designers have intended it to be the machine that will finally show that fusion power plants can really be built.

The ITER project formally began in 2006, when its international partners agreed to fund an estimated €5 billion (then $6.3 billion), 10-year plan that would have seen ITER come online in 2016. The most recent official cost estimate stands at more than €20 billion ($22 billion), with ITER nominally turning on scarcely two years from now. Documents recently obtained via a lawsuit, however, imply that these figures are woefully outdated: ITER is not just facing several years’ worth of additional delays but also a growing internal recognition that the project’s remaining technical challenges are poised to send budgets spiraling even further out of control and successful operation ever further into the future.

The documents drafted a year ago for a private meeting of the ITER Council, ITER’s governing body, show that at the time, the project was bracing for a three-year delay—a doubling of internal estimates prepared just six months earlier. And in the year since those documents were written, the already grim news out of ITER has unfortunately only gotten worse. Yet no one within the ITER Organization has been able to provide estimates of the additional delays, much less the extra expenses expected to result from them. Nor has anyone at the U.S. Department of Energy, which is in charge of the nation’s contributions to ITER, been able to do so. When contacted for this story, DOE officials did not respond to any questions by the time of publication.

The problems leading to these latest projected delays were several years in the making. The ITER Organization was extremely slow to let on that anything was wrong, however. As late as early July 2022, ITER’s website announced that the machine was expected to turn on as scheduled in December 2025. Afterward that date bore an asterisk clarifying that it would be revised. Now the date has disappeared from the website altogether.

ITER leaders seldom let slip that anything was awry either. In February 2017 ITER’s then director general, the late Bernard Bigot, discussed its progress with DOE representatives. “ITER is really moving forward,” he said. “We are working day and night…. The progress is on schedule.” The timeline he presented implied that everything was on track. Construction of the ITER complex’s foundation, which incorporates an earthquake protection system with hundreds of tremor-dampening rubber- and metal-laminated plates, should have been almost complete.

From there, assembly of the reactor itself was planned to begin in 2018. At the time of Bigot’s remarks, two of its major pieces—a massive magnetic coil to wrap around the doughnutlike tokamak and a large section of the vacuum vessel that makes up the tokamak’s walls—were supposed to be ready to ship within the month and by the end of the year, respectively. Instead, the coil would take almost three more years to complete, as would the vessel sector. The pieces were completed in January and April 2020, respectively. In fact, a large proportion of the big components of the machine were behind schedule by a year or two years or even more. Soon ITER’s official start of assembly was bumped from 2018 to 2020.